Nastaran Daneshgar, MD1, Peir-In Liang, MD1,4, Renny S. Lan, PhD.5,6, McKenna Horstmann1, Lindsay Pack, PhD.5, Gourav Bhardwaj, PhD2, Christie M. Penniman2, Brian T. O’Neill, MD, PhD2,3, Dao-Fu Dai, MD, PhD1

1Department of Pathology, Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City

2 Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center and Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA

3 Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Iowa City, IA, 52242, USA

4Department of Pathology, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

5 Arkansas Children’s Nutrition Center, Little Rock, AR, USA

6Department of Pediatrics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR,

Corresponding author:

Dao-Fu Dai, MD, PhD

Abstract

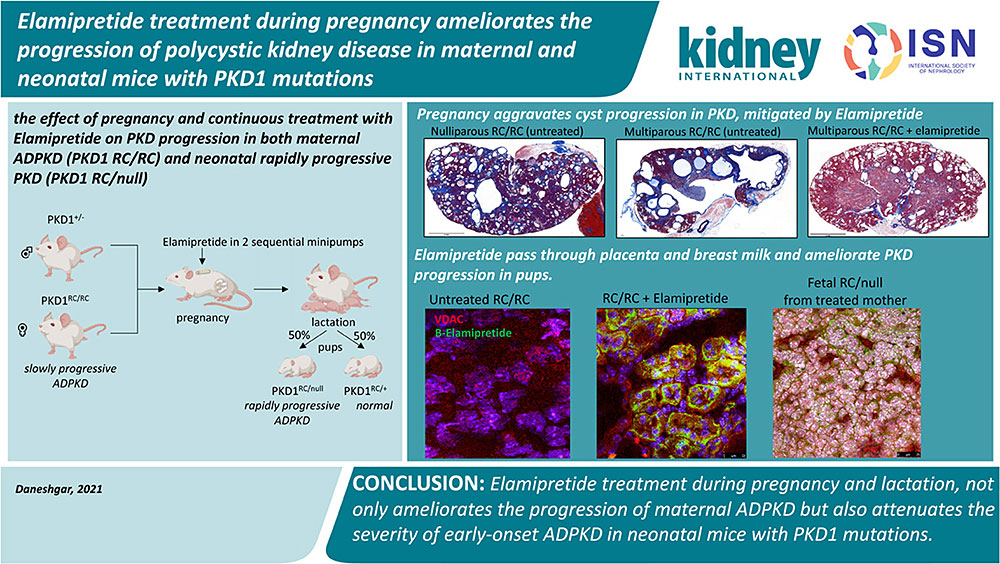

Pregnancy is proposed to aggravate cyst progression in polycystic kidney disease (PKD) but Tolvaptan, the only FDA-approved drug for adult ADPKD, is not recommended for pregnant PKD patients because of potential fetal harm. We investigated the safety and efficacy of Elamipretide, a mitochondrial-protective peptide. Elamipretide ameliorated the progression of PKD in pregnant PKD1 RC/RC mice, in parallel with attenuation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation and improvement of mitochondrial supercomplex formation. We further found that Elamipretide can pass through the placenta and breast milk and ameliorate aggressive infantile ADPKD without any observed teratogenic or harmful effect on early development.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords:

polycystic kidney disease, elamipretide, pregnancy, mitochondria

Translational Statement

There are limited therapeutic options available for reproductive-age women and pediatric patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), since the only FDA-approved drug Tolvaptan is teratogenic at a high dose and the safety in infants and children is unclear. We demonstrate that Elamipretide, a mitochondrial-targeted peptide, is safe and efficient in maternal and neonatal mice with PKD1 mutations. Elamipretide has excellent safety profiles and is currently tested in multiple phase II and phase III clinical trials, our current report supports a potential clinical trial of Elamipretide for the treatment of ADPKD, particularly for patients that cannot take Tolvaptan.

Introduction

Tolvaptan, a selective vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist, is the first FDA approved drug to delay autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) progression to kidney failure in adults1. The efficacy and safety of Tolvaptan in infants and children remain to be elucidated. According to FDA recommendation, Tolvaptan should be discontinued during pregnancy and lactation as it may cause fetal harm based on animal data. However, pregnancy itself may increase the risk for ADPKD progression. Increased physiological demands, hemodynamic overload, and urinary retention in the collecting system during pregnancy2 could aggravate the enlargement of kidney cysts. In addition, hypertension and kidney function impairment in ADPKD women significantly increases the risk of pregnancy complications3. Therefore, there is a critical need to develop a novel drug with an excellent safety profile for pregnant ADPKD women.

Most individuals with ADPKD remain asymptomatic until the fourth decade of life, but approximately 2-5% have early-onset and rapidly progressive ADPKD4 with kidney cysts as early as the prenatal period, resembling an autosomal recessive PKD. Genetic analysis of early-onset progressive ADPKD patients indicates that in addition to the expected germ-line defect in PKD1 genes from the affected parent, additional insult from genetic variants (such as hypomorphic mutations) of PKD genes from the unaffected parent resulted in a severe compromise in polycystin-1 (PKD1) function5. These findings are consistent with the gene-dosage effect of PKD1 gene. This has been shown in a knock-in mouse model PKD1 p.R3277C (RC point mutation), a functionally hypomorphic allele that aggravates ADPKD phenotypes when the other allele of PKD1 is deleted. Although PKD1 +/null mice are normal, PKD1 RC/null mice have rapidly progressive disease resembling infantile (fetal) ADPKD, and PKD1RC/RC mice (hereafter referred to as RC/RC mice) develop a slowly progressive disease resembling typical ADPKD6.

At the molecular level, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, predicted to increase in pregnancy7, have been implicated in ADPKD progression. Elamipretide is a tetrapeptide targeting mitochondria through interaction with cardiolipin in the inner mitochondrial membrane8,9, subsequently enhancing respiratory supercomplex formation, increasing the efficiency of electron transfer, ATP production and reducing mitochondrial ROS production10 with protective effects in hypertensive cardiomyopathy and heart failure11,12. In this study, we demonstrated that a mitochondrial protective peptide, Elamipretide, given during pregnancy significantly ameliorates the progression of PKD in both maternal ADPKD (RC/RC) and neonatal rapidly progressive PKD (RC/null), associated with improved mitochondrial supercomplex formation.

Methods

Animal models and experimental design

Animal experiments were approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee. Pkd1 p.R3277C knock-in mice were obtained from Mayo Clinic. They were the result of the Pkd1 p.R3277C mutation introduced using the exact codon found in ADPKD probands (Pkd1 c.9805.9807AGA>TGC) as described. The PKD1RC/null mice were generated by crossing PKD1RC/RC mice with PKD1+/- mice. The PKD1 +/- were generated by breeding PKD1flox/flox mice (B6.129S4-Pkd1tm2Ggg/J, JAX, 129S4/SvJae background) with germline Sox2-Cre transgenic mice (Edil3Tg(Sox2-cre)1Amc, JAX, C57BL/6J background). All mice were fed with regular chow (Teklad Standard Diet). Elamipretide, originally named Szeto-Schiller peptide 3113, was purchased from New England Peptide (Gardner, MA). The biotinylated Elamipretide was synthesized by adding the biotin to the N-terminal of the tetrapeptide Biotin-D-Arg-Dimethyltyrosine-Lysine-Phe-NH2 (Pepmic Co., Suzhou, China). The experimental design is illustrated in Fig. 2A. We delivered continuous elamipretide treatment using two sequential subcutaneous insertions of the Alzet 1004 minipump for 3-4-month-old female RC/RC mice, initiated approximately one week after breeding, then replaced by the second pump ~5 weeks after the first pump. All mice were euthanized around 6 months of age.

Results

Multiparity aggravates progression of ADPKD, mitigated by Elamipretide

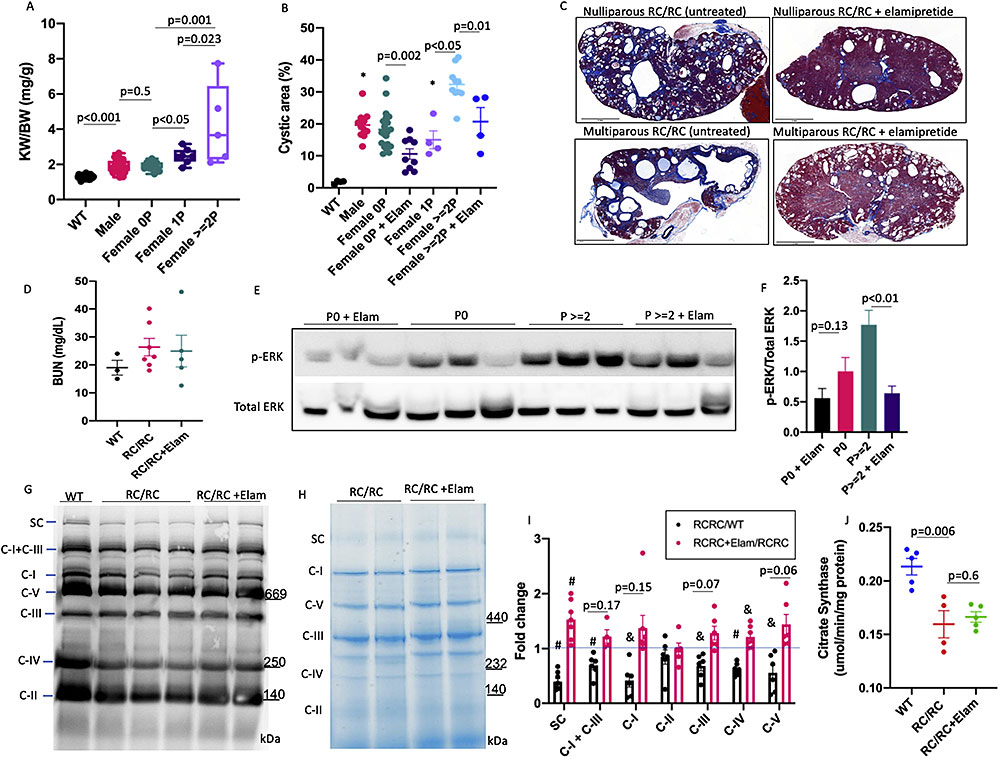

Multiparity has been associated with higher serum creatinine in ADPKD women with four or more pregnancies3; however, the impact of pregnancy on the progression of cysts in ADPKD is not well understood. Using a breeding strategy of male PKD1+/- and female RC/RC, we examined the effect of pregnancy and continuous treatment with Elamipretide (3mg/kg/day in 2 sequential Alzet 1004 pumps for ~10 weeks) on PKD progression. Kidney weight normalized to body weight (KW/BW) in RC/RC mice was significantly higher than that in WT mice and was comparable among male and female nulliparous, and slightly higher in primiparous (one cycle of pregnancy) RC/RC mice (Fig. 1A). In contrast, multiparous RC/RC female had a ~2-fold increase in KW/BW than the nulliparous (p=0.001) or primiparous female of similar ages (p=0.023, Fig. 1A). Quantitative pathological analysis revealed that the relative cystic areas in male, nulliparous and primiparous RC/RC female mice are similar, approximately 10-20%, higher than that in WT mice (p<0.01 for all), which had no cysts. Multiparous RC/RC mice had >30% cystic area, significantly higher than male, nulliparous or primiparous RC/RC mice (p<0.001) (Fig. 1B). Multiparous mice also had significantly higher fibrosis area or combined cystic and fibrosis area compared with those in nulli- and primiparous females (Fig. S1A-B). Continuous Elamipretide treatment significantly ameliorated the percentage of cystic area or combined cystic and fibrotic area, for both multiparous and nulliparous / primiparous females (Fig. 1B-C, Fig S1A-B). The Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was slightly higher in RC/RC mice compared with WT, but there was no significant difference among all groups (Fig. 1D).

To obtain mechanistic insight into the accelerated ADPKD progression during pregnancy, we examined Extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) phosphorylation previously reported to be increased in PKD14. There was a significant increase in p-ERK in RC/RC kidneys from multiparous compared with the nulliparous group and treatment with Elamipretide significantly reduced p-ERK in both nulli- and multiparous groups (Fig. 1E-F, Fig. S1E). Using blue-native gel with or without OXPHOS cocktail immunoblotting, we showed a substantial decrease in all mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes and supercomplexes in RC/RC mice compared with WT (ratio of RC/RC to WT < 1 for all, p<0.05 for all except for complex II). Elamipretide partially restored the levels of supercomplexes and individual respiratory complexes (ratio of RC/RC+ Elam to RC/RC > 1 for all), although these were only significant for respiratory supercomplex (p=0.009) and complex IV (p=0.016, Fig. 1G-I). Citrate synthase measurements showed significant decrease in RC/RC mice compared with WT and elamipretide had no effect (Fig. 1J), suggesting that the beneficial effect of Elamipretide is at the level of supercomplex formation.

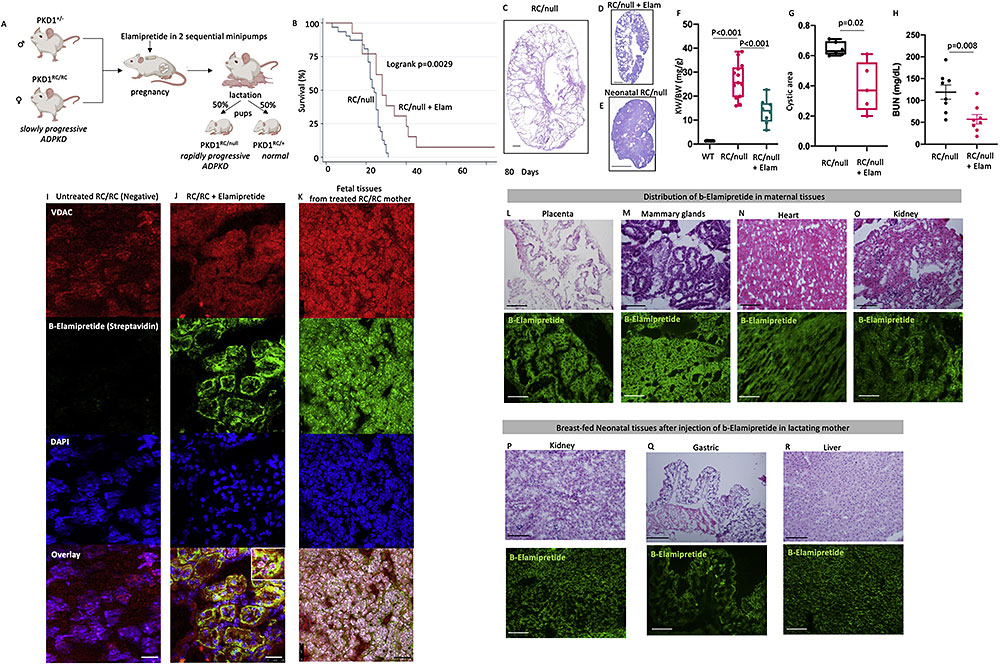

While evaluating the effect of Elamipretide on pregnant RC/RC female, we found that RC/null mice born from these treated RC/RC mother had significant prolongation of lifespan compared with RC/null mice born from untreated mothers (Fig. 2A-B), which typically develops kidney failure and mortality around 18-28 days6. In parallel with lifespan extension, cystic area, KW/BW and BUN were significantly decreased in the RC/null pups from Elamipretide-treated mothers (Fig. 2C-H). Elamipretide treatment also decreased Ki-67 staining, a marker of proliferation, in the kidneys of RC/null mice (p<0.05) and the RC/RC mice (p=0.14, Figure S1F). The RC/+ littermate controls from Elamipretide-treated mothers have normal development into adult mice. Extensive pathological examinations did not reveal any anatomical or microscopic anomalies in the heart, brain, liver, and spleen of RC/null and RC/+ mice (Fig. S2A-B). Next, we injected pregnant RC/RC mice with biotin-labeled elamipretide (b-elamipretide) to track its tissue distribution. In the untreated RC/RC mouse kidney section, Alexa 488-streptavidin staining was negative, suggesting the absence of non-specific staining of endogenous biotin (Fig. 2I). Alexa 488-streptavidin highlighted b-elamipretide and showed that it co-localized with VDAC, a mitochondrial marker, in both maternal and fetal kidneys (Fig. 2J-K). We confirmed the delivery of b-elamipretide to neonatal kidney tissue, shown by co-localization with PAX-8, a marker of renal tissue (Fig. S2C). B-Elamipretide was also present in maternal placenta, mammary glands, heart, kidney (Fig. 2L-O) and liver but not spleen (Fig. S2D). To assess whether elamipretide can pass through breast milk, we injected a lactating RC/RC mother with the labeled peptide 24 and 6 hours prior to tissue collection of breast-fed neonates. We observed intracellular localization of b-Elamipretide in several organs of breast-fed neonates including kidney, gastric mucosa, and liver, but not brain (Fig. 2P-R, Fig. S2E). To further confirm the successful delivery of Elamipretide, we performed mass spectrometry analysis. As shown in Fig S3A-B, the ms2 spectra of purified unconjugated Elamipretide show a full-length peptide with m/z of 640.39 (the molecular weight of Elamipretide) and multiple fragments with m/z of 130.16, 303.18, 320.70, and 459.27, of which 320.70 is the most abundant fragment, as previously reported15. Mass spectrometric analysis of neonatal kidney tissues from Elamipretide-treated mother confirm the presence of the full-length m/z of 640.39, and the 130.16 and 320.70 fragments (Fig. S3C-D).

Discussion

Here we reported that continuous Elamipretide treatment during pregnancy and lactation period not only ameliorates the progression of maternal ADPKD but also attenuates the severity of early-onset ADPKD in neonatal mice with PKD1 mutations. Our data demonstrated that Elamipretide enhances mitochondrial supercomplex formation in RC/RC kidneys, in parallel with amelioration of ADPKD progression and attenuation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The ERK1/2 are members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase superfamily that regulate cell proliferation and are known to be activated by ROS16. The mitigation of ROS-sensitive ERK1/2 phosphorylation is consistent with the indirect antioxidant effects of Elamipretide, which has been shown to attenuate ROS and oxidative damage in cardiovascular, kidney and brain, by protecting mitochondria9.

Limited studies have previously shown that ADPKD increases the risk of maternal and neonatal complications. In an earlier case-control study, hypertensive ADPKD women with four or more pregnancies had lower creatinine clearances than age-adjusted hypertensive ADPKD women with fewer than four pregnancies3. A more recent study showed pregnancy in ADPKD women slightly increased the risk of fetal distress but it was significantly associated with worsening of hypertension, proteinuria, edema and a higher proportion of elevated serum creatinine in mothers17. However, the effect of pregnancy on the progression of kidney cysts remains unclear. Our current study demonstrates the prominent effect of multiparity on the progression of cystic disease in RC/RC mice with substantial cystic progression in RC/RC mice with two or more pregnancies compared with RC/RC mice with one pregnancy. Mechanistically, increased hemodynamic stress and the surge of circulating estrogen during pregnancy may have increased oxidative stress in cystic kidneys and contributed to the disease progression. Our finding that mitochondrial protection by Elamipretide attenuates cyst progression and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in kidneys, including those with multiple pregnancies, support this hypothesis.

With the advance of new therapies and management for ADPKD patients, the chance for ADPKD women to pursue multiple pregnancies is increasing. Tolvaptan inhibits tubular cell proliferation and fluid secretion by reducing intracellular cAMP1. Side effects include thirst, polyuria, hypotension, and hypernatremia as this V2 receptor antagonist was developed to treat Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion. Previous studies showed that long-term treatment with Tolvaptan (from 1 to 6-month-old) decreased KW/BW of RC/RC mice by ~10%18. In the current study, Elamipretide treatment for two months (from 4 to 6-month-old) decreased KW/BW by ~20% in the nulliparous RC/RC mice and by ~40% in the multiparous RC/RC group. Although Tolvaptan has been shown to delay the progression of ADPKD in adult patients19, experimental data in rats showed that Tolvaptan given during pregnancy has embryo-fetal toxicity at low exposure and can pass easily into breastmilk20.

Elamipretide is a new class of small peptide drugs protecting mitochondria with an excellent safety profile and is currently undergoing multiple phase II and III clinical trials8 for mitochondrial diseases, heart failure and cardiomyopathies. Although the safety data during pregnancy and lactation is not available in humans, our current study in pregnant ADPKD mice did not show any evidence of fetal harm or teratogenicity. Using biotin-labeled peptide, we confirmed that Elamipretide passes through the placenta and breastmilk, which may explain the beneficial effect in treating early-onset ADPKD in utero and during the lactation period. Our current study is limited by the application of only one pre-clinical model, mice with PKD1 RC mutation. In summary, our pre-clinical study supports future clinical trials of Elamipretide for ADPKD, particularly in pregnant ADPKD women and early onset ADPKD in neonatal and pediatric patients.

Disclosure statement

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH): K08 HL145138 and AHA 858512 (DFD), and VA Merit Review Award Number lO1 BXOO4468 (to B.T.O). We thank Collen S. Stein for technical assistance with blue native gel experiment.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. [Quantitative analysis of (A) fibrotic area, and (B) combined cysts and fibrotic area in WT, male and nulliparous, primiparous and multiparous female RC/RC mice untreated or treated with elamipretide at ~6-month-old. (n=4-5) (C) Kidney weight normalized to body weight in nulliparous and multiparous RC/RC mice ± Elamipretide. (D) Body weight of groups in C. (E) Ponceau S. staining of blot in Figure 1E. (F) Quantification of Ki-67 positive cells in the kidneys of RC/RC and RC/null mice ± Elamipretide (n=5-10).]

Figure S2. [(A) Representative PAS staining of heart, brain, liver and spleen sections of RC/null neonates from Elamipretide treated mom showing no structural/developmental abnormality. (B) Histological examination of a 4-week-old RC/+ mouse born from an Elamipretide-treated mother, showing serial coronal sections of right brain (Left panels), anterior forebrain, Lateral ventricle, Hippocampal region, Midbrain and Cerebellum, Heart, Kidney, Spleen and Liver. Hemotoxylin and Eosin stain. Scale bar: 0.5 mm. (C) localization of biotinylated elamipretide and PAX8 in neonatal kidney cells. Biotinylated peptide was visualized with streptavidin-AlexaFluor488 and Renal tissue marker, PAX8, was visualized with AlexaFluor555 (scale bar:25μm). (D) Representative H&E and immunofluorescence staining of biotinylated peptide in liver and spleen of RC/RC female treated with b-elamipretide (scale bar:100μm). (E) Representative H&E and immunofluorescence staining of biotinylated peptide in brain of breast-fed neonatal RC/null pups from elamipretide treated mom. Biotinylated peptide was visualized with streptavidin-AlexaFluor488 (scale bar:100μm).]

Figure S3. [Tandem mass spectrometry MS2 (MS/MS) spectra of (A) pure synthetic Elamipretide used for treatment and (B-C) two representative tissue lysates from Elamipretide-treated kidneys, showing spectra of a full-length peptide with m/z of 640.39 and a characteristic fragment of Elamipretide with m/z of 320.70.]

Supplementary methods.

Supplementary References.

Supplementary information is available on Kidney International's website.

References:

1. Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, et al. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2407-2418. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1205511

2. Gonzalez Suarez ML, Kattah A, Grande JP, Garovic V. Renal Disorders in Pregnancy: Core Curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(1):119-130. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.06.006

3. Chapman AB, Johnson AM, Gabow PA. Pregnancy outcome and its relationship to progression of renal failure in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;5(5):1178-1185.

4. Audrézet M-P, Corbiere C, Lebbah S, et al. Comprehensive PKD1 and PKD2 Mutation Analysis in Prenatal Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(3):722-729. doi:10.1681/ASN.2014101051

5. Bergmann C, von Bothmer J, Ortiz Brüchle N, et al. Mutations in Multiple PKD Genes May Explain Early and Severe Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(11):2047 LP - 2056. doi:10.1681/ASN.2010101080

6. Hopp K, Ward CJ, Hommerding CJ, et al. Functional polycystin-1 dosage governs autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease severity. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(11):4257-4273. doi:10.1172/JCI64313

7. Sharma JB, Sharma A, Bahadur A, Vimala N, Satyam A, Mittal S. Oxidative stress markers and antioxidant levels in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94(1):23-27. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.03.025

8. Szeto HH. Stealth Peptides Target Cellular Powerhouses to Fight Rare and Common Age-Related Diseases. Protein Pept Lett. 2018;25(12):1108-1123. doi:10.2174/0929866525666181101105209

9. Szeto HH, Birk A V. Serendipity and the discovery of novel compounds that restore mitochondrial plasticity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96(6):672-683. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.174

10. Chavez JD, Tang X, Campbell MD, et al. Mitochondrial protein interaction landscape of SS-31. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(26):15363 LP - 15373. doi:10.1073/pnas.2002250117

11. Dai D-F, Chen T, Szeto H, et al. Mitochondrial targeted antioxidant Peptide ameliorates hypertensive cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(1):73-82. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.044

12. Dai D-F, Hsieh EJ, Chen T, et al. Global Proteomics and Pathway Analysis of Pressure-Overload–Induced Heart Failure and Its Attenuation by Mitochondrial-Targeted Peptides. Circ Hear Fail. 2013;6(5):1067-1076. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000406

13. Szeto HH. First-in-class cardiolipin-protective compound as a therapeutic agent to restore mitochondrial bioenergetics. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171(8):2029-2050. doi:10.1111/bph.12461

14. Daneshgar N, Baguley AW, Liang P-I, et al. Metabolic derangement in polycystic kidney disease mouse models is ameliorated by mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):1200. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-02730-w

15. Wyss J-C, Kumar R, Mikulic J, et al. Differential Effects of the Mitochondria-Active Tetrapeptide SS-31 (D-Arg-dimethylTyr-Lys-Phe-NH2) and Its Peptidase-Targeted Prodrugs in Experimental Acute Kidney Injury . Front Pharmacol . 2019;10:1209. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2019.01209.

16. Guyton KZ, Liu Y, Gorospe M, Xu Q, Holbrook NJ. Activation of Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase by H2O2: ROLE IN CELL SURVIVAL FOLLOWING OXIDANT INJURY (∗). J Biol Chem. 1996;271(8):4138-4142. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.8.4138

17. Wu M, Wang D, Zand L, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a case-control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(5):807-812. doi:10.3109/14767058.2015.1019458

18. Hopp K, Hommerding CJ, Wang X, Ye H, Harris PC, Torres VE. Tolvaptan plus pasireotide shows enhanced efficacy in a PKD1 model. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(1):39-47. doi:10.1681/ASN.2013121312

19. Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, et al. Tolvaptan in Later-Stage Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1930-1942. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1710030

20. Furukawa M, Umehara K, Kashiyama E. Nonclinical pharmacokinetics of a new nonpeptide V2 receptor antagonist, tolvaptan. Cardiovasc drugs Ther. 2011;25 Suppl 1:S83-9. doi:10.1007/s10557-011-6357-x

Figure Legends:

Figure 1. Pregnancy aggravates cyst progression in PKD, mitigated by elamipretide. (A) Kidney weight normalized to body weight in male and nulliparous, primiparous and multiparous female RC/RC mice (n=5-25) at ~6-7-month-old. (B) Quantitative analysis of cystic area in WT, male and nulliparous, primiparous and multiparous female RC/RC mice. (C) Representative Masson’s trichrome staining of kidney in nulliparous and multiparous RC/RC untreated or treated with elamipretide (scale bar: 2mm) (n=4-20) (D) BUN levels in WT, non-pregnant RC/RC and RC/RC mice treated with Elamipretide (n=3-7) (E) Representative western-blot of p-ERK and Total ERK in nulliparous and multiparous RC/RC untreated or treated with elamipretide and (F) quantification. (G) Immunoblotting of OXPHOS complex and supercomplexes following (H) blue-native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in WT, RC/RC untreated or treated with elamipretide and (I) quantification of immunoblot and blue native gel depicted as a ratio of RC/RC vs. WT and RC/RC+elam vs. RC/RC (& p<0.05, # p<0.01). (n=4-6). (J) Citrate synthase in WT, RC/RC and RC/RC mice treated with Elamipretide (n=4-5).

Figure 2. Elamipretide pass through placenta and breast milk and ameliorate PKD progression in pups. (A) Experimental design (created by biorender) (B) Survival curve of RC/null pups from untreated or Elamipretide treated mom (n=5-10), Representative PAS staining of kidney sections of RC/null pups (~21 day-old) from (C) untreated or (D) Elamipretide treated mom and (E) Neonatal RC/null (scale bar: 1mm). (F) Kidney weight normalized to body weight in WT and RC/null pups from untreated or Elamipretide treated mom (n=4-10, multiple litters) (G) Quantification of cystic area in RC/null pups from untreated or Elamipretide treated mom (n=5, multiple litters). (H) BUN levels in untreated and elamipretide treated RC/null mice (n=8) (I) Negative b-elamipretide staining in the untreated RC/RC mouse. Intracellular localization of biotinylated elamipretide by streptavidin in (J) maternal at low and high magnification (inset) and (K) neonatal kidney cells. Biotinylated peptide was visualized with streptavidin-AlexaFluor488 and mitochondrial marker, VDAC, was visualized with AlexaFluor555 (scale bar:25μm). Representative H&E and immunofluorescence staining of b-elamipretide in maternal (L) placenta, (M) mammary glands, (N) heart and (O) kidney and (P) Kidney, (Q) stomach and (R) liver of breast-fed neonatal RC/null pups from elamipretide treated mom (scale bar:100 μm).

Renal Biopsy Specimen Preparation & Transport Instructions to learn more about how to send a renal biopsy to us.